The grocer stocks up on City Hall leadership

Jeff Brown is a hugger.

He got that from his father, along with the family business.

Like his father, he is a grocer, an unapologetic businessman, straight up.

Like his father, he sees business as a way to make money, sure, but also to help people.

The help his ShopRite and Green Grocer markets provide is twofold: Good food for lower-income customers trapped in “food deserts,” and also providing good-paying union jobs for the community. The union part is deliberate, that I’ll get to in a moment.

His Center City campaign headquarters, where I go to do this interview, is harder to find than a CIA safe house. The entrance is through a garage, and I’ll let it go at that.

Why that location, hard by the Schuylkill? It’s cheap, explains Brown, 59, speaking like a man who has thrived in an industry with a 1% profit margin. Message: He knows how to manage money.

What he’s offering voters, he says, is a solutions-centered leader who is not encumbered by political “experience.” (His platform is at www.JeffBrownforMayor.com ) The former City Council candidates -- Allan Domb, Cherelle Parker, Derek Green, Helen Gym, Maria Quinones Sanchez -- should be disqualified on the basis of nonperformance while in office, he says, sliding former controller Rebecca Rhynhart into the “formers,” but she could not author legislation.

“I don’t know how they justify running,” he says. “Their performance is miserable.”

He had been even more brash about them, speaking to someone else.

A few hours after we spoke on Friday, Brown apologized for using the word “lynch.” The Inquirer made that a Page One story.

Brown was quoted as saying the Council candidates “have their little deals amongst themselves and if the citizens knew, they’d lynch them.”

The racial klaxons went off, with former Councilman and mayoral candidate Derek Green saying he was “disgusted” by Brown’s words. Green is Black, as is Parker, who through a spokesperson said Brown’s words “speak for themselves.” It was all faux outrage.

On the other hand, “Works are louder than words,” said the Rev. Marshall Mitchell, a prominent Black clergyman, who is a Brown supporter.

In our conversation, Brown used a different L-word: Liar, and he applied it to Domb.

Domb is airing a TV commercial showing apparently different statements made by Brown on funding the police to groups in the Northeast and West Philly. The commercial is “a complete lie,” Brown says.

“The Inquirer caught Jeff Brown saying one thing to one group of voters in West Philadelphia and the complete opposite to Northeast Philadelphia voters,” says Domb spokesman Jared Leopold. “It’s clear that Jeff Brown is just upset that he got caught by the Inquirer trying to take two sides of the same issue."

The grocer and Domb, a.k.a., the Condo King, are both thought of as moderate, white, millionaires, wooing perhaps the same voting base, which may explain why they are going after each other.

Brown gets a little personal when he says, “Allan’s work is all rich white people,” while Brown serves “everyday people.” Interestingly, Brown lives on Rittenhouse Square, which is the heart of Domb’s real estate empire.

Domb “is more like what you think of what people don’t like about rich people, you know, where they’re sort of self-absorbed, you know, only focused on money,” says Brown.

“Allan is proud of his record helping people in neighborhoods across the city, including investing in small businesses and donating his City Council salary to schools and educational programs in Philadelphia,” says Leopold. “Instead of spending his collapsing campaign with bizarre attacks on Allan Domb, maybe Jeff Brown should explain why he shuttered a store in West Philadelphia and cost workers their jobs after receiving a taxpayer subsidy for that store."

---

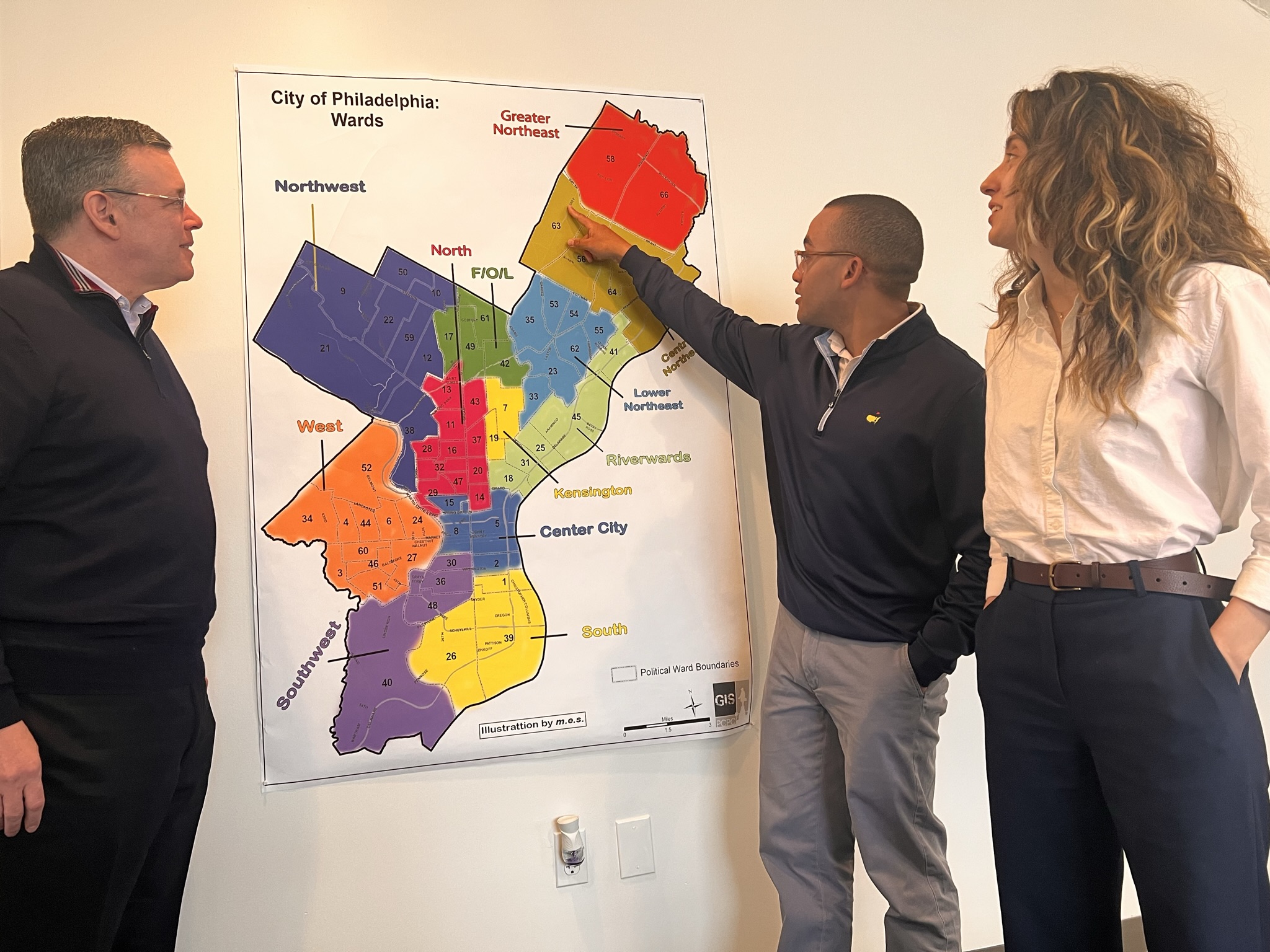

I had wondered where Brown’s base was, until enlightened in a separate conversation with Brown’s political director, Bernie Strain. The base, Strain says, are Brown’s eight markets located in Philadelphia.

Strain first met Brown after the opening of the ShopRite in Roxborough about 30 years ago.

Strain’s three young sons were involved in athletics and Brown, who has four sons, would often show up at games and talk to people. “He would ask what we needed, uniforms, or hot dogs and soda to sell,” remembers Strain, who said their friendship began then.

Strain described the supermarkets almost as community centers in or near nonwhite communities. In them, many Black entrepreneurs get to sell their wares. (Brown has a degree in entrepreneurship from Massachusetts’ Babson College.)

Some people, who remember that Brown fought ferociously against Jim Kenney’s “soda tax,” whisper that he is running to become mayor to reverse the tax. Mayoral candidate Helen Gym has said it openly.

Like Brown, I opposed the tax but ask if he would take a pledge to not repeal the tax.

“Yes,” he says, because he will be serving different people as mayor, even though he believes the tax falls heaviest on the poor.

If you didn’t get into this to kill the soda tax, what was your epiphany, I ask.

He replies with an anecdote that goes back to Covid time, when businesses — mostly Black and brown, he says — were going bust fast because they were having trouble accessing PPP funds.

He and three colleagues started a nonprofit called the PA 30-Day Fund to help resolve that issue, and points to that as an example of him being a problem solver.

He spoke to an elderly Black lady whose hair salon had just gone under. She “was really, really upset about her circumstances and crying on the phone. And that was the moment,” he says. Because of a lack of leadership, “the government completely failed this person . . . And, I’m like, you know, I’ve had enough of this.”

That lit the fuse, and he expects to spend maybe $4 million to win a job that pays $240,000.

And he will accept the salary, unlike Domb, who will donate it back to the city, as he did with his Council salary.

It’s not that Brown needs the money. He says he and his family donate far more than that to charity each year.

He thinks of the salary as a contract with the citizens.

“You pay me, I am responsible to you. That’s a relationship,” he says. “I take that salary and l’m obligated to work for the people.”

His stores are unionized — he says he prefers it that way and takes pride in paying a living wage and benefits.

So he was hurt by Cherelle Parker’s nonsense charge that he pays some of his employees $9.65 an hour. No one makes less than $12 an hour, part-time, and $15 an hour minimum, fulltime, according to his unions, which have endorsed his candidacy.

Brown believes in second chances. That applies to the ex-cons he is famous for hiring, and also to Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw.

“I’m concerned about her job performance. A lot of people died in the last few years,” he says.

“Her outcomes have been bad,” he says, but he feels it would be unfair to fire her without giving her a chance to explain the challenges she faces. “So I would owe her that meeting and listen to what she has to say.”

Second chances also explains why he has hired so-called “returning citizens” for years. (I call them ex-cons because that’s what they usually call themselves.)

Brown says 500 of his current employees are ex -offenders, out of a workforce of 2,300, but he has hired thousands of ex-cons over the years, with a next-to-nothing 2% recidivism rate, Brown says.

That alone probably reduced the crime rate, because when ex-cons can’t get legal work, they will turn to illegal work. He created a national nonprofit, Uplift Solutions, to implement such hiring programs.

Continuing in the justice vein, Brown supports some of D.A. Larry Krasner’s restorative justice ideas, but does not accept Krasner’s policy of not prosecuting shoplifters, and soft-pedaling illegal gun arrests.

“I think he has policies that harm public safety,” he says.

“Shoplifting is way up in the city,” he says, with some shoplifters who get stopped in his store, saying, “Larry said it’s legal.”

He swears that has happened.

As to those arrested with unregistered guns, “if they otherwise have a clean record, Larry is not implementing any kind of penalty.” That is a “very dangerous policy. . . It’s insane. It lacks common sense.”

On a related issue, he rejects so-called “safe” injection sites. Would it make sense to put one in Kensington “and cement their position as the drug capital of Philadelphia?” he asks.

He believes bike lanes should have community input, that the issue is not “cut and dry,” and illegals living here convicted of serious crimes should be turned over to the feds, unlike the current policy that protects even foreign felons.

He admits he lacks deep knowledge of how city government works -- he got sand bagged at a forum with a highly technical question about city financing by “impartial” moderator Michael Nutter (a few weeks before he endorsed Rhynhart). Brown says he can hire experts and bills himself as a leader who can solve complex problems.

In a sports analogy, Rob Thomson can’t swing a bat, but he managed the Phillies into the World Series.

Jeff Brown wants nothing less, and if elected, he’ll be giving out a lot of hugs.