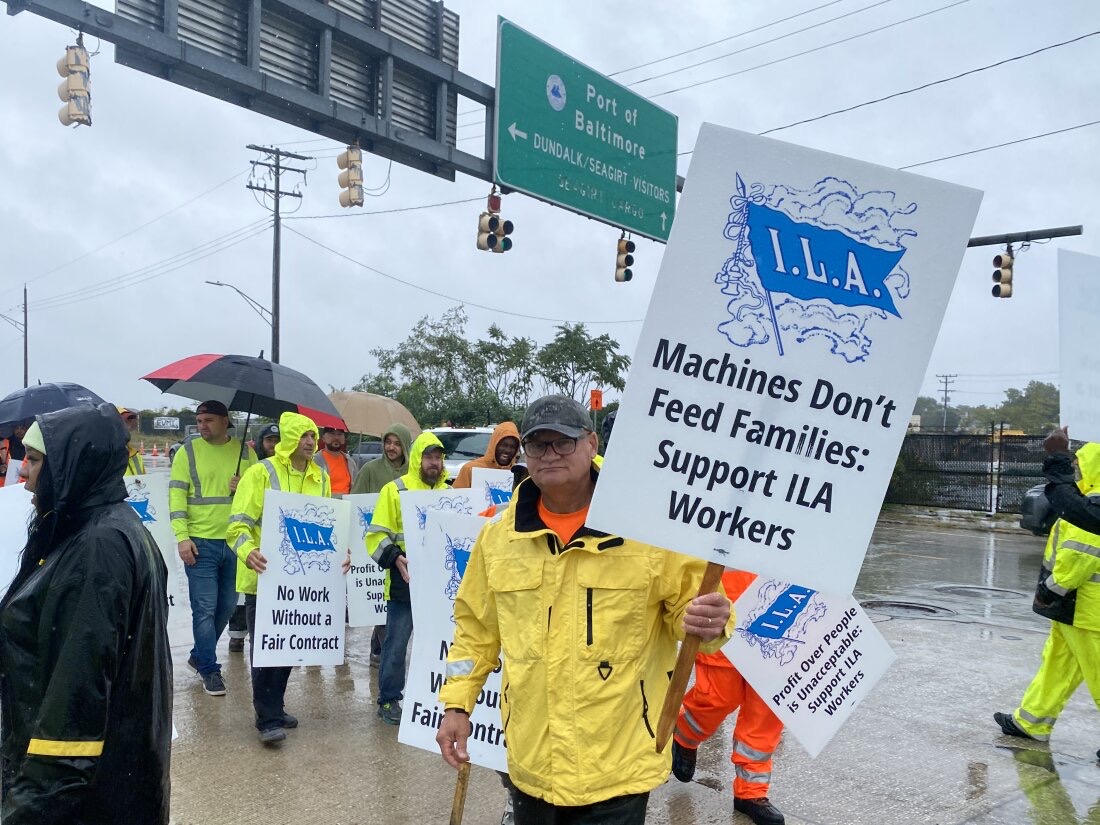

How to settle the automation issue

After a brief, just-for-show strike, Atlantic and Gulf coast longshoremen returned to work, having agreed to an almost 62% pay hike(!) over 6 years, but leaving unresolved their real fears about automation. These will be discussed in January.

Their fears are not unfounded.

This is way more than you need to know.

In real terms, automation means using machines for tasks that used to be performed by humans.

In theory, it increases efficiency and lowers costs.

Example: In ancient newspaper print shops, a printer would have to select a piece of type, a letter A for example, and place it in a small metal device in his hand. Then select the next, say letter D.

It was extraordinarily time-consuming. And then came the Line-O-Type, a machine that allowed an operator at a keyboard to generate perhaps 10 lines of type a minute.

That reduced the number of printers needed, and because less labor was needed, the cost was less, too. But many printers could have lost their jobs.

I deliberately chose the printing industry because I know what happened.

The then-owner of the Daily New and the Inquirer, was a well-run, humanistic company.

Rather than fire the unnecessary printers outright, they were given choices. Some chose to take a buyout and leave. As I recall this was about $25,000 (depending on seniority) and many chose to leave. It was a lot of money 40 years ago.

Others chose to stay, and were retrained into jobs required by the new cold type, computer technology, that replaced the hot type, Line-O-Type technology.

Auto manufacturing accounted for almost 20 million jobs in 1979, now down to 585,000, although foreign competition probably had more to do with the drop than automation.

Old-fashioned assembly lines where workers did simple, repetitive tasks — think Lucy and Ethel on the chocolate candy production line — are largely a thing of the past. Robots help human workers, relieving them of tedious repetition.

I’m pretty sure dock workers didn’t bitch when fork lifts were introduced, saving their busting backs.

Shipping containers made their jobs simple and easier. I believe it was Scott Galloway who called shipping containers one of the most important inventions of mankind. I think he’s right, because it sped cargo, and lowered costs.

So what do about the dilemma of dock workers who push back against progress (and costs) for the understandable desire to save their livelihoods?

Well, as in my industry, guarantee them their jobs.

Do not guarantee the jobs or salary of future workers.

When the worker is given a guarantee of his/her job, he/she will be hard-put to reject that to protect some future worker who may never arrive. Yes, the owners will have to be a little patient, but they are not going broke.

As current workers quit, die, take buyouts or retire, the issue will be resolved in less than a generation, with no hard feelings on any side.