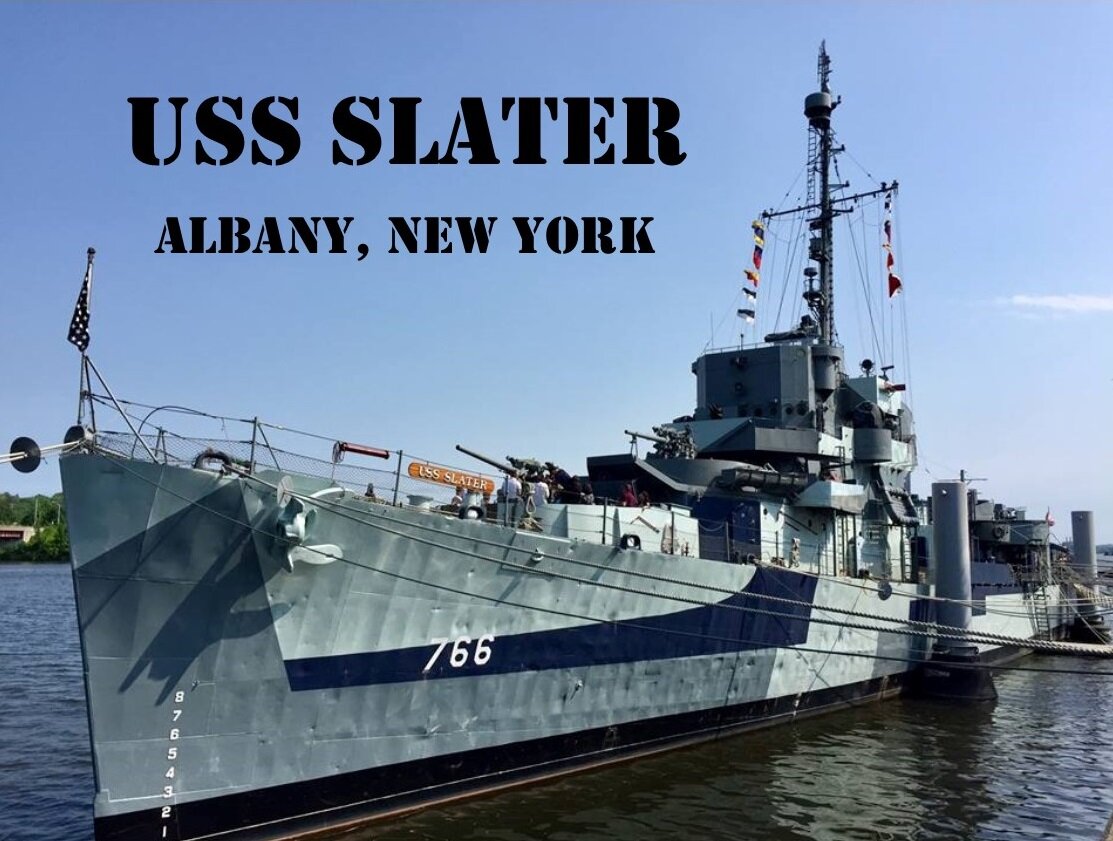

From World War II, the last lady of the line

They call her a lucky ship. And a long-living ship.

During her service in the waning days of World War II, the USS Slater, DE-766, a destroyer escort, never lost a soul.

I finally got to visit this living piece of history a few days ago, and this story will explain how I became attached to this ship, the only American WWII destroyer escort still afloat in the U.S.

Destroyer escorts are named after deceased naval heroes, and 766’s namesake was seaman second class Frank O. Slater, who died at his gun station aboard the USS San Francisco firing at an attacking Japanese aircraft during the battle of Guadalcanal in 1942. He was awarded the Navy Cross.

Frank Slater’s mother, Nora L. Slater, was invited by the Navy to christen the 306-foot Slater, which was commissioned on May 1, 1944. She was built by the Tampa Shipbuilding Company, in Tampa, FL., for $3.3 million — $57.4 million in today’s dollars. Instead of champagne, Nora used water drawn from the well that Frank had dug on the Slater farm, where they had been sharecroppers.

Slater carried a complement of 15 officers and 201 enlisted men, one of whom was gunner’s mate Elam Slater, who requested to serve on the ship named for his older brother. He sailed with her in 1944-45. Things like this don’t happen only in the movies.

DE sailors lived in tight quarters for long periods, and bonded only as men under the threat of death can. Their story is a naval version of Band of Brothers, with one difference: Slater never suffered the unquenchable sorrow of a burial at sea.

Slater’s role was to escort convoys across the Atlantic, and to attack German submarines that tried to stop the ocean superhighway that delivered arms and materiel from America to Europe.

America ordered 1,005 of these small, swift sub-killers when Nazi U-boats were sinking merchant ships faster than America could build them. Within a couple of years, thanks mostly to the trim DEs, German subs were sunk faster than they could be replaced. Only 563 DEs were built before the war ended. The Allies won the Battle of the Atlantic largely because of these lion-hearted vessels.

Slater escorted five convoys across the Atlantic. After the European theater was won, she was sent to the Pacific where she engaged in support operations.

In 1951, she was transferred to the Greek Navy and renamed Aetos, which is Greek for “eagle.” History paced her decks.

For 40 years, she served as a patrol craft, and later as a training vessel, when the Greeks retired her and donated her to the Destroyer Escort Sailors Association, which raised $250,000 to bring her home as a museum ship.

She was in poor shape, but back in the hands of American sailors who deeply loved her.

The Destroyer Escort Sailors Association disbanded last year, sadly, because the Greatest Generation veterans were passing through the hourglass of time. Tears came to my eyes when I read that the handful of surviving heroes gathered for a final farewell and dutifully turned their memorabilia over to the Slater. She is now a memorial to them and their exploits, to educate future generations about their sacrifice and patriotism. As long as she is afloat, the DE sailors’ candle will continue to burn, brightly.

In 1993, she was docked in New York City, where volunteers began restoring her while a permanent home was sought. That was found in 1997, when she was moved up the Hudson, to Albany, the capital of New York, her forever home.

The next year she was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Among the many people who engineered, financially and politically, her move to Albany was Gordon Lattey, one of my oldest friends, and my most important mentor. He passed last year.

Here’s a chunk of what I wrote about Gordon at that time:

“He dabbled in business, in PR, marketing, politics, and a hobby called the USS Slater, a World War II destroyer escort that a group of altruists had gotten a hold of and were refitting in Albany, N.Y. Gordon had helped them out, and introduced me to the project. I became a supporter of the only WWII DE afloat in the United States.”

I had always been an Army guy, the branch in which my family served, but over a couple of decades of attending Army/Navy games with Gordon, I went through military conversion therapy and came out a gob. Well, Philly is a Navy town, anyway.

I had been a supporter for about 20 years, without ever seeing the object of my affection in the flesh, or in the 5/8th inch steel which is her skin. Very thin for a warship, and why destroyers are nicknamed “tin cans.” She was built for speed, not for comfort, as I learned during my tour, led by volunteer historian Carl Camurati.

Carl is one of 120 volunteers who donate 15,000 hours a year to maintain the ship in its World War II vintage condition. Even on a new ship, maintenance is nonstop. On an older vessel, afloat, it is nonstop on speed.

Obviously, parts are no longer being manufactured. My friend Gordon’s specialty was “materials acquisition,” which in plain English meant scrounging spare parts from vessels mothballed in old Navy yards, such as Brooklyn and Philadelphia, and beyond.

When original parts can’t be found, they must be hand-fashioned or purchased, and that can be expensive, and Slater takes no tax money. It is proudly self-sufficient, having raised more than $2 million from private donors.

Once I made my initial gift, I received my USS Slater cap, and started receiving Slater Signals, the ship’s museum’s excellent monthly online newsletter, supplemented by the quarterly print magazine, Trim but Deadly, written by Tim Rizzuto, executive director of the Destroyer Escort Historical Museum.

It was largely through Signals — a wonderful mixture of emotion, fact, gossip and seagoing detail — that I learned of the devotion DE sailors had for each other, and for the vessels on which they served, and for Slater, the last of her breed. She is the bridge between the WWII sailors, almost all gone now, and the latter-day volunteers and visitors who cherish this marvelous relic. I came to love Slater.

Because of my 6-3 height, my age, and my bum leg, I could not safely get to all points on the small vessel.

So small and light, at sea destroyers were like bucking broncos, dipping and tipping wildly. Some DE sailors joked they should have been entitled to submarine and aviation pay, because the bow was often below the surface of the sea, or sometimes pointed almost at the sun. Once you got your sea legs on a tin can, there was nothing you could not sail.

I was privileged to visit the quarters of the first captain to command Slater in WWII, Marcel J. Blancq.

He had a single bunk under a porthole, a typing desk and typewriter, another desk, and a closet. The officers’ restroom had an actual commode, while the enlisted men did their business sitting on a plank.

The officers’ mess was well-appointed, having a dining table that doubled as an operating table, for simple surgery. For any serious injury, sailors would be transferred to a larger ship that had an actual operating theater and trained surgeons.

Four cooks turned out meals four times a day, and there were even two bakers who whipped up 200 loaves a day for hungry seamen.

The ship was a 24/7 operation, most especially when she was protecting a convoy, which could number up to 150 ships. All eyes were constantly peeled, assisted by radar and sonar, plus a radio frequency homing device — pretty advanced stuff for WWII.

Slater is painted in a handsome gray, blue, and black “dazzle camouflage” pattern, she bristles with cannons, machine guns, and various kinds of depth charges. She had a top speed of 21 knots, and her twin rudders meant she could turn on a dime.

From the online history: “Meals are again cooked in her galley and served on her mess decks. Decks are swept and swabbed. . . Her radar rotates, signal flags flutter, ventilators hum, and freshwater again flows through her plumbing. The colors are raised every morning and lowered every evening.”

Words don’t do this lucky lady justice. There is amazing information at www.ussslater.org

May you have fair winds and following seas.