A hero cop is down, but not forgotten

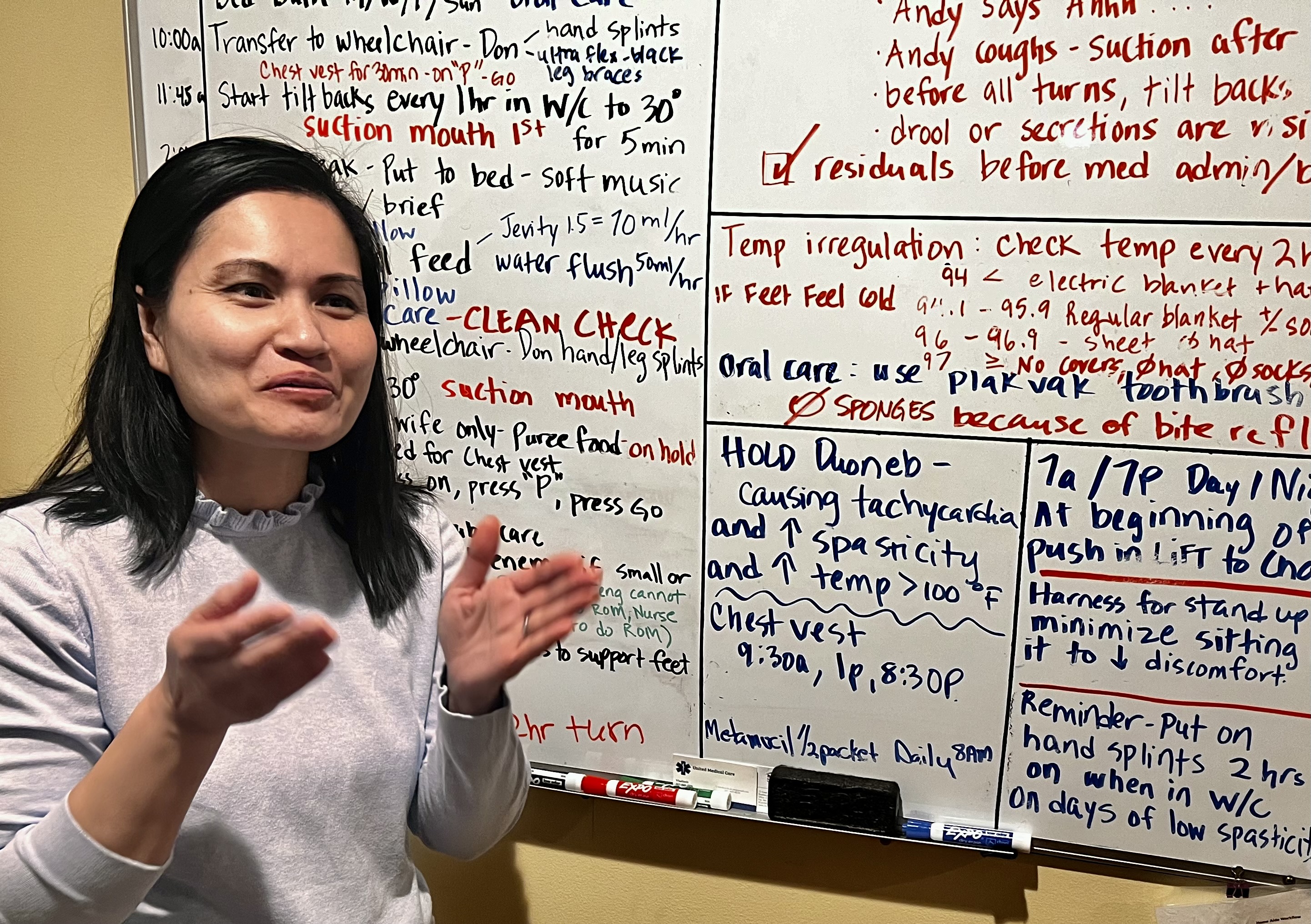

The huge whiteboard tells the story.

The whiteboard is covered with instructions in Teng Chan’s neat handwriting, instructions that meticulously detail the daily medical needs of her husband, Andy, who is paralyzed, and vulnerable.

The whiteboard stands vigil between Andy and death, because he is grievously wounded.

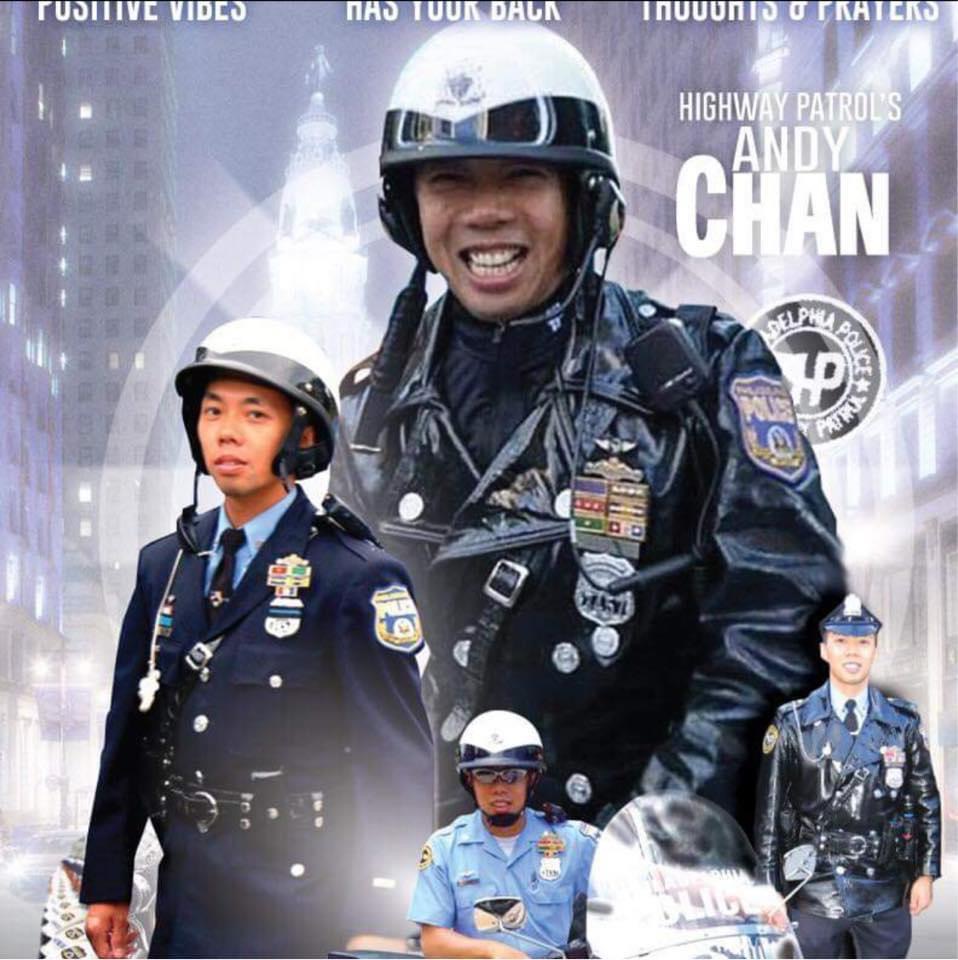

Andy, 53, was a proud member of the Philadelphia Police Department’s elite Highway Patrol unit.

Being appointed to the unit in 2004 was the fulfillment of Andy’s dream, an ambition he had from the time he was a kid hanging out in his parents’ Chinatown restaurant.

The restaurant was called Sampan, and its regulars included officers from Highway Patrol.

The HP officers wore tight black leather motorcycle jackets, bald eagle helmets, and gleaming, knee-high, Chippewa boots when they came into Sampan, just a few blocks from the Roundhouse, the former police headquarters.

Andy Chan liked their flash, and he liked their mission — helping people, fighting crime.

He wanted to help people. He wanted to be a cop. Specifically, he wanted to be a Highway Patrolman.

Despite its name, Highway Patrol doesn't patrol highways. It once had responsibility for the interstates within Philly — 76, 676, 95 — but now the state police does that.

HP is sent to Philly’s toughest neighborhoods to patrol and assist police officers in those districts. A second HP function is to provide escorts, such as for visiting dignitaries, and funerals. That is when officers ride the cherished Harley-Davidson Road King motorcycles they refer to as “wheels.” The rest of the time they are in two-man patrol cars, other than when they ride to and from work.

Andy had an urge to serve, and he was all in.

He became a Philadelphia police officer in 1996, assigned to North Philadelphia’s high-crime 39th District. He distinguished himself, and eight years later, he made HP.

His partner, Kyle Cross, 47, tells me that’s when Andy changed how he greeted people. Instead of “Hello,” or “Hi,” Andy would burst out, “Highway!” The job became how he defined his life.

He was exuberant, rambunctious, always had time for everyone, says Kyle, and everyone liked him. As one of the few Chinese-Americans on the force, he was instantly recognizable. And he was a leader. You can learn more about him on the Andy Chan Strong Facebook page.

On the night of May 12, 2015, a speeding New York-bound Amtrak train derailed in Port Richmond, causing eight deaths and more than 200 injuries.

HP partners Andy and Kyle were among the first to get there, arriving to find the rail cars scattered like Lego blocks, with dead and severely injured passengers on the slope of an embankment.

They immediately began tending to injured passengers until medics arrived, and assisting passengers away from the crippled train.

“Andy took the lead and I followed him,” says Kyle. “He was one of those people who you trusted.” He remembers Andy’s poise and calm amid the chaos.

Andy is experiencing a different kind of calm now, an unwanted and cruel calm.

In his 23rd year on the force, on Jan. 3, 2019, the highly-decorated officer was riding his his Road King near Pennypack Park in Northeast Philadelphia when he was blindsided by a motorist and was catapulted off his motorcycle. His life changed forever on that cold night.

He was rushed to Jefferson Torresdale Hospital, where Police Commissioner Rich Ross told reporters Andy had sustained “very significant” head injuries and doctors were “hopeful.”

He said Andy “is one heck of a police officer. He is well-known and well-regarded in the police department.”

After the accident, Kyle tells me Ross visited Andy almost daily in the hospital and to this day is there for Andy and his family.

In the hospital, Andy was in a coma for almost two months, says Teng, who is 45. They have been married for 14 years and have three children. Their lives have been changed forever, too.

After Jefferson, Andy was transferred to the Good Shepherd rehab hospital and later to Magee Rehabilitation Hospital, both in Center City.

Magee is an excellent facility, but there are limits on what they can do, and also what is covered by insurance, which ran out.

For six months after coming out of the coma, Andy was barely awake. Even now, though improved, he’s in a state doctors call “Minimally conscious.” Teng believes “He knows what’s going on. He just can’t say it.”

He is confined to a wheelchair, paralyzed, unable to move or speak. He can breathe on his own, but is fed with two tubes — one to his stomach, one to his small intestine. The only movement he can manage is his eyes.

Right from the jump, Teng knew she would never send Andy to a facility.

“You hear nightmares about, you know, what happens when you go to a facility,” she says. Visions of neglect and bed sores danced in her head. No!

The decision was made to keep him at home, no matter the amount of work, “and we are making it work,” she says. Her daily challenge is “juggling” Andy’s care, and that’s where the large whiteboard comes in.

It is a diagram, the daily instructions for what must be done to keep Andy healthy, for Teng and the nurse plus the medical aide who are in the house 24/7. Andy is helpless to help himself, and his precarious condition requires constant attention.

He has good days and bad days, Teng tells me when I visit their spacious split-level home in Philadelphia. I am there on a bad day, when he is less conscious and less comfortable.

His heart rate was elevated. There are concerns about seizures, and pneumonia, and oxygen if needed. On a really bad day, “he is sweating, he is sick, everything we have is not working and we have to go to the hospital,” Teng tells me.

I introduce myself to Andy, telling him who I am and why I am there. His eyes look at me, but I don’t know if I am being understood. It is painful to see this once strong, athletic man with his head tilted back and his arms and legs frozen into an awkward position.

It used to be worse, Teng says. Until recently his head was tilted back into a “scary” position.

“When he’s conscious, we can tell he’s awake,” says Teng. “He makes long blinks for yes. And when he acknowledges, he also vocalizes, so it sounds like he’s trying to say something.”

Kyle says the house is actually a mini-hospital, with supplies stockpiled and more arriving every day.

“It is like running a hospital here,” says Teng. “You have medical supplies, you have to keep up with prescriptions, you have to deal with schedules for the agencies. . . And then you have the kids — you have to remember to pickup and take care of the kids.”

Most of this falls on Teng’s shoulders and she handles it with grace.

“She is a sweetheart,” says Kyle, who is now a sergeant in the police department's labor relations unit.

There is family nearby who help with the children, important because Teng works two or three days a week as a pharmacist in a cancer center to help cover expenses.

She says Kyle is “amazing, he’s always here.” She thinks of him as a brother and jokes “Kyle’s last name is Chan.”

The children — I am withholding details about them to honor the family’s request for privacy — maintain a relationship with their father by playing music for him, and reading to him.

“Every morning they say ‘Good morning, Daddy,’” says Teng. “We have family time right before bed. And then we pray. We pray every night.”

Teng was told that most of Andy’s recovery would come in the first year. Andy is now in his fifth year of paralysis. “It’s gonna be a miracle at this point, you know, if he recovers even more,” says Teng.

That’s one reason prayer is stocked in the home along with the medical supplies.

Teng gets help from the law-enforcement and other communities, and she is grateful for the financial and emotional support — and the prayers — she gets from others, including HP and the Fraternal Order of Police, which often calls to check in with her.

The reality is that insurance and workman's comp do not pay all the bills, which is why there is an annual Andy Chan fund-raiser run by the Families Behind the Badge nonprofit. If you would like to donate, you can use this link

Donations would be appreciated, a miracle even more.